Lawful marriage, stability of the Colony

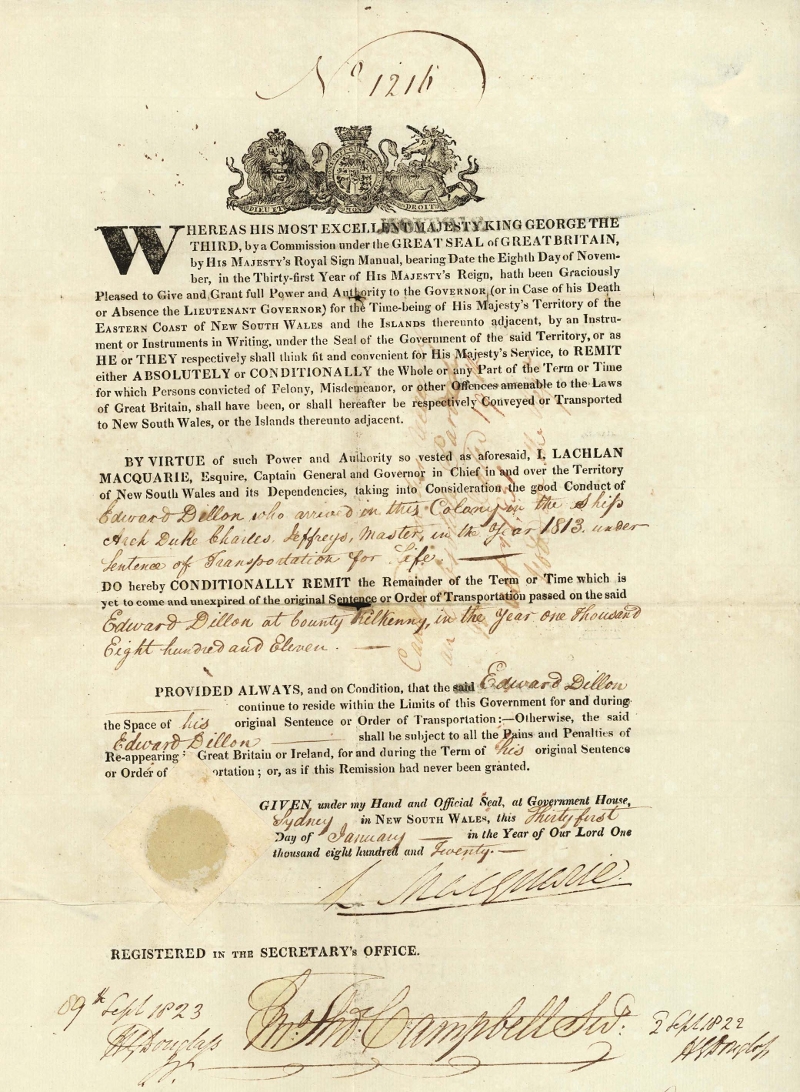

During Lachlan Macquarie’s governorship of NSW (1810-1821), marriage was encouraged. For the convict classes this was carefully controlled by the State. The belief was that children born of convicts might be ‘infected’ by the ‘convict stain’. Given that the convict classes made up three-quarters of the registered adult population, authorities feared that the next generation would be morally tarred: a situation which threatened to destabilise the Colony. Convicts, therefore, were required to have the explicit permission of the Governor to marry the person of their choice. These controls were tightened under Governor Ralph Darling (1825-1831). Now, a convict’s master or mistress plus a clergyman, had to approve a marriage prior to an application being made to the Governor. In many instances, permission was refused.

On this page

- Convicts: Permission to marry refused

- Convicts: Approved applications to marry

- Marriage Banns

- Free men and women

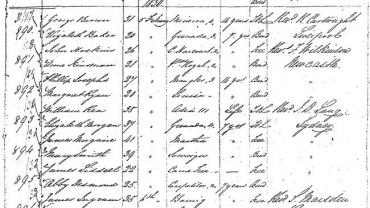

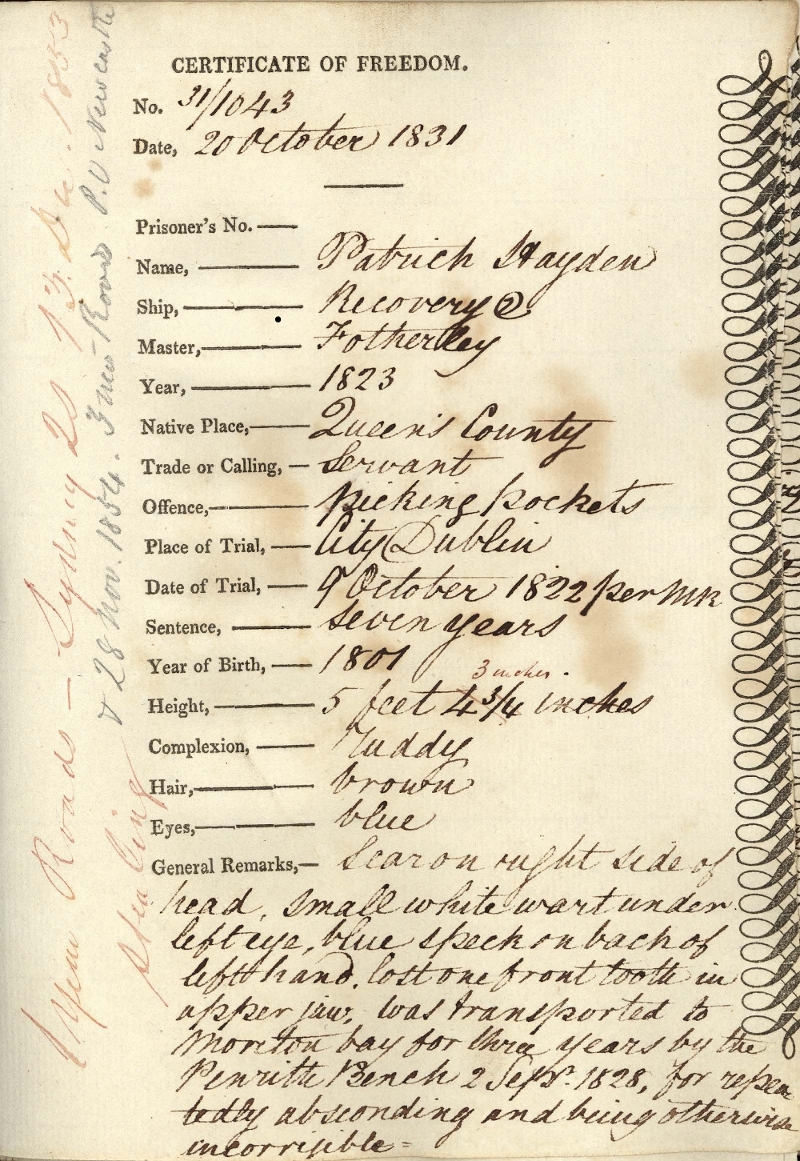

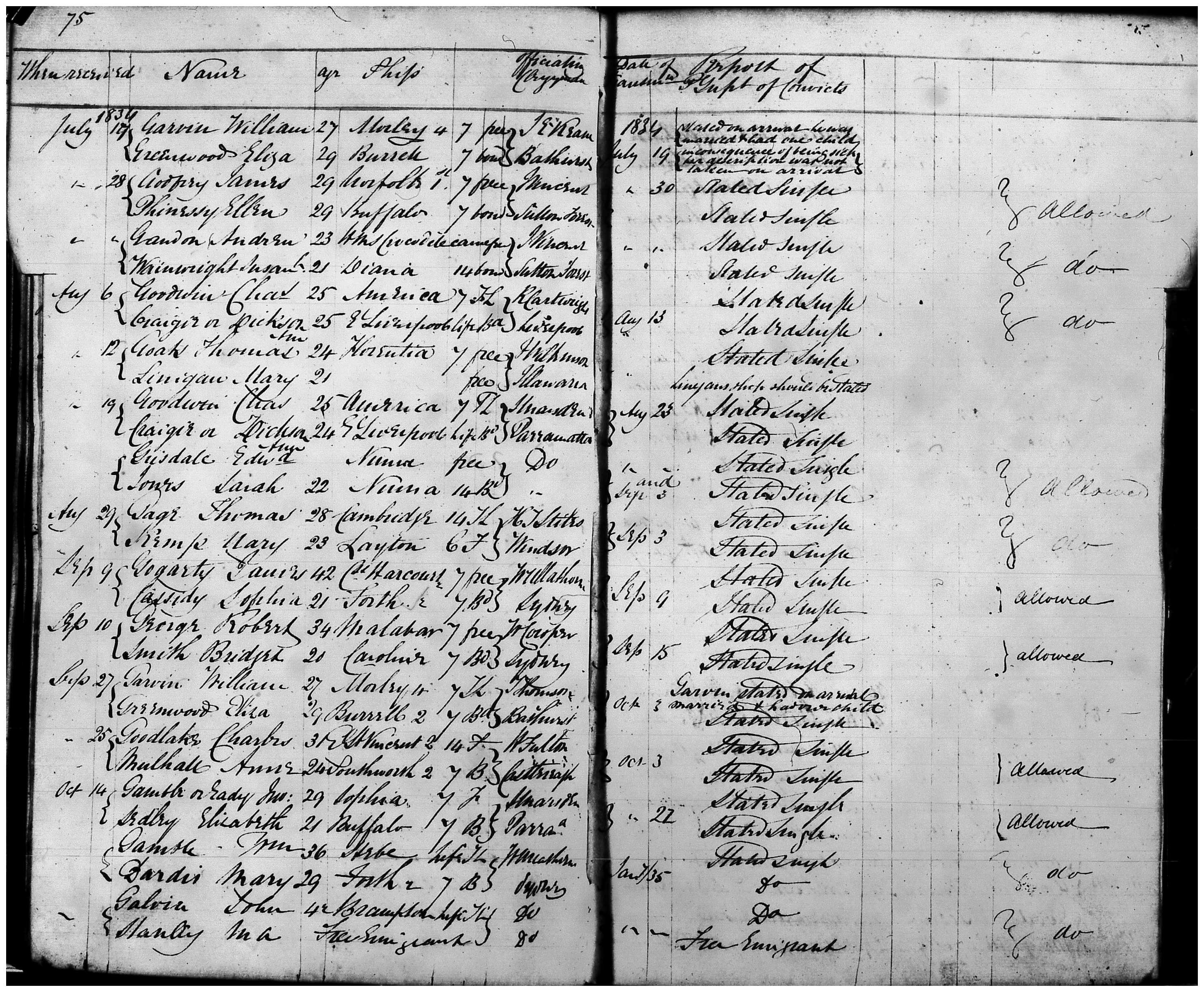

The period 20 October to 28 December 1831 provides a useful snap shot. Twenty-two couples were refused permission to marry. The most common reason was ‘the female being already married’. Married women, it was thought, were better treated in the Colony, so some women falsely declared themselves married when disembarking in Sydney. When they did eventually seek permission to wed, they were refused.

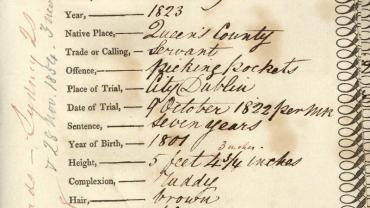

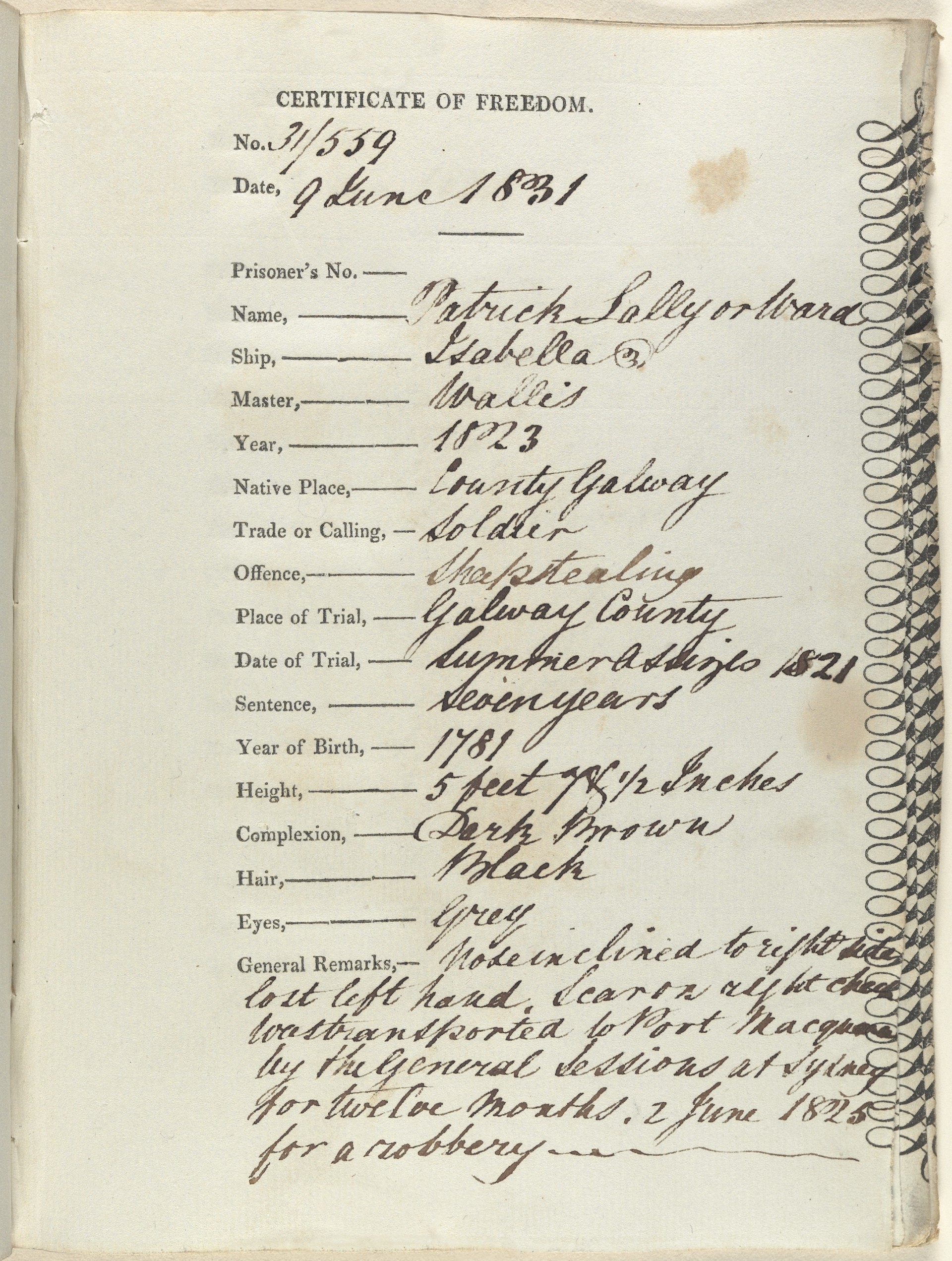

While permission to marry was refused to some applicants, others were successful. For example, between 13 May and 23 June 1828, permission to marry was granted to 24 couples. The youngest applicant was 17 year old Elizabeth Parker (per Harmony), and the oldest, 51 year old Thomas Cox (per Asia [1]). Most applicants had been sentenced to seven years transportation. Some had received life sentences. Those still bonded to a master or mistress had to remain in service until free.

The seven year transportation sentence caused some confusion for applicants and administrators. Transportation to NSW meant forced separation for thousands of couples. An absence from a spouse for seven years—the length of most sentences—it was believed, entitled one to remarry. The Solicitor General advised in 1841 that such parties married at their own ‘peril’. After all, a first wife or husband could still be living, and therefore, couples risked a charge of bigamy.

Once the Governor had granted permission, forthcoming marriages were publicised through ‘marriage banns’. A clergyman would announce the union on three occasions, providing the opportunity for anyone who opposed the match to come forward.

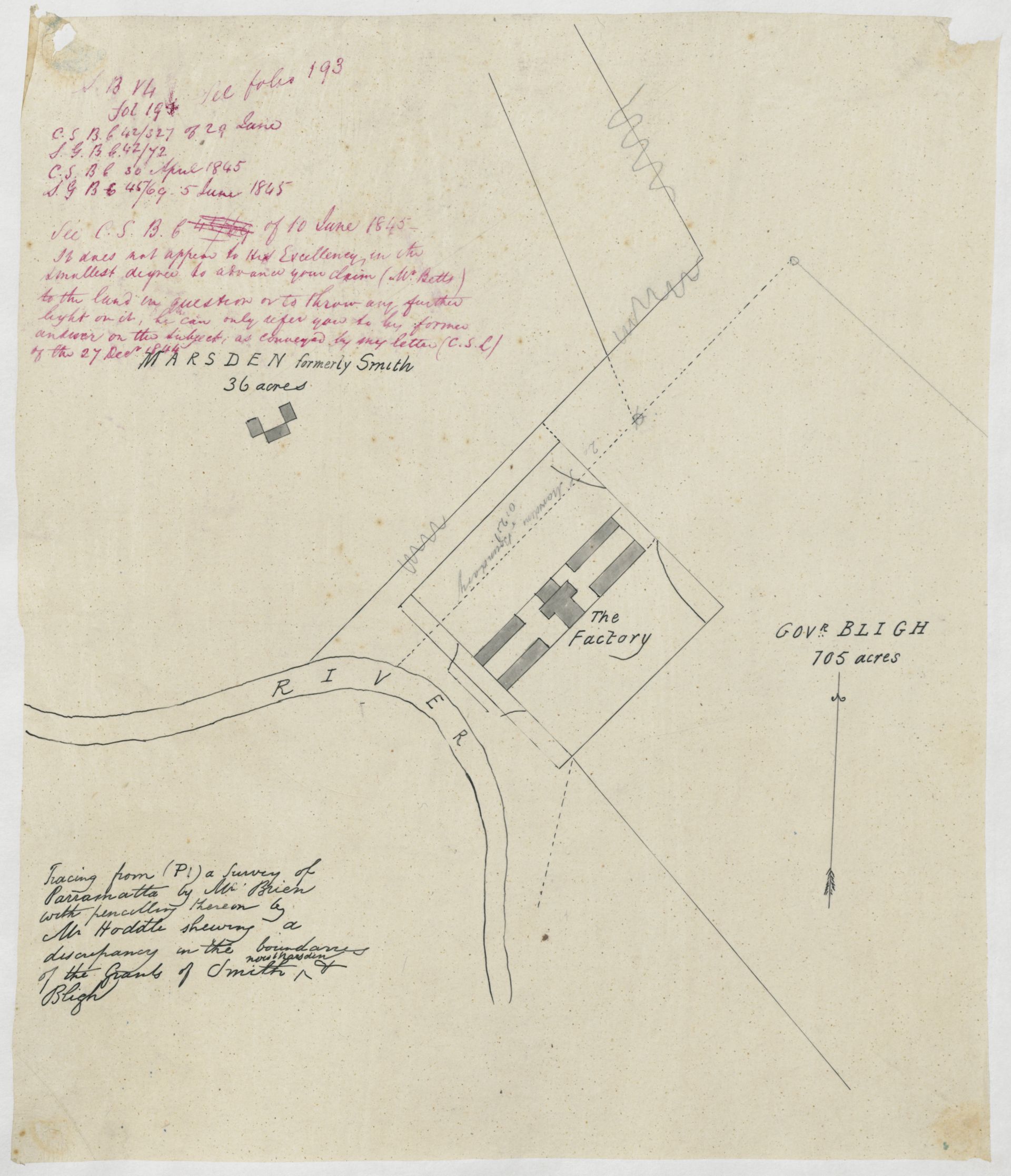

Two couples, Thomas Brooks/Mary Ward, and Thomas Badham/Elizabeth Rogers, expected to have their unions publicised through marriage banns at St Philip’s, Sydney, in September 1832. Each of the four had been given good character references and clergyman, William Cowper, had granted approval.

The State, however, dismissed the Badham/Rogers application. Elizabeth had listed herself as ‘married’ when arriving in the Colony, now she was claiming to be widowed. A letter from Elizabeth’s aunt, Mrs Vanderburg notifying the young woman that her London-based husband was ‘no longer’—thus confirming her status as a widow—was rejected as a falsehood by authorities. This was unsurprising given that aunt Vanderburg’s letter from ‘London’ had, in fact, been postmarked in Sydney. Undeterred, the couple soon reapplied, and were married six months later at St Luke’s, Liverpool.

Unlike the convict classes, free men and women did not have to seek permission to marry. But their numbers were few in early colonial NSW, and it was cohabitation rather than marriage, that defined the majority of unions between men and women. Free couples could obtain a marriage licence. Sometimes a special licence had to be secured. If, for example, a woman was an ‘infant’—under the age of 16 years—then her father’s consent to the marriage was required prior to the issuing of the licence.

It was not until the end of the penal era and the rise of the free settler society in the mid-19th Century that the institution of marriage became the norm in NSW. There was ambiguity around whether marriages solemnised outside the Church of England were legally valid. A series of reforms between 1834 and 1855 confirmed the validity of marriages solemnised through the ‘Churches of Scotland and Rome’. Later, this was extended to Jews and Quakers.

Content first published in the Marriage: Love and Law exhibition catalogue