Property, respectability

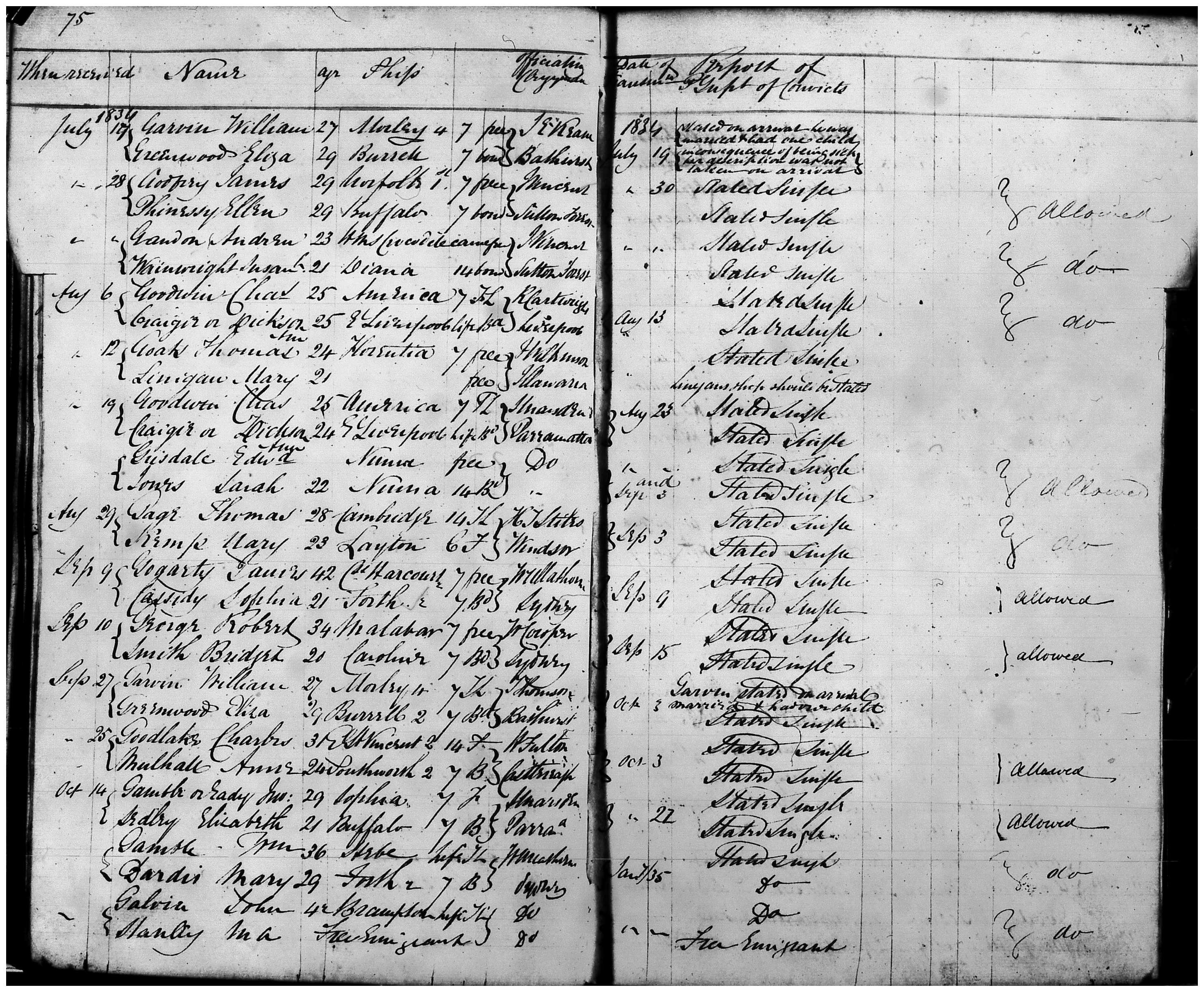

Upon marriage, the woman could claim her land. It was thought that a bachelor of respectability would be more inclined to marry a woman who had property. The birth of children would likely follow, and this would boost the Colony’s respectable class. Under the marriage portions scheme women would hold the property title. Upon a woman’s death, the title would pass on to her children and not her husband. In 1830 and 1831, a total of 42 married women, including Hannah Tompson, were granted land portions.

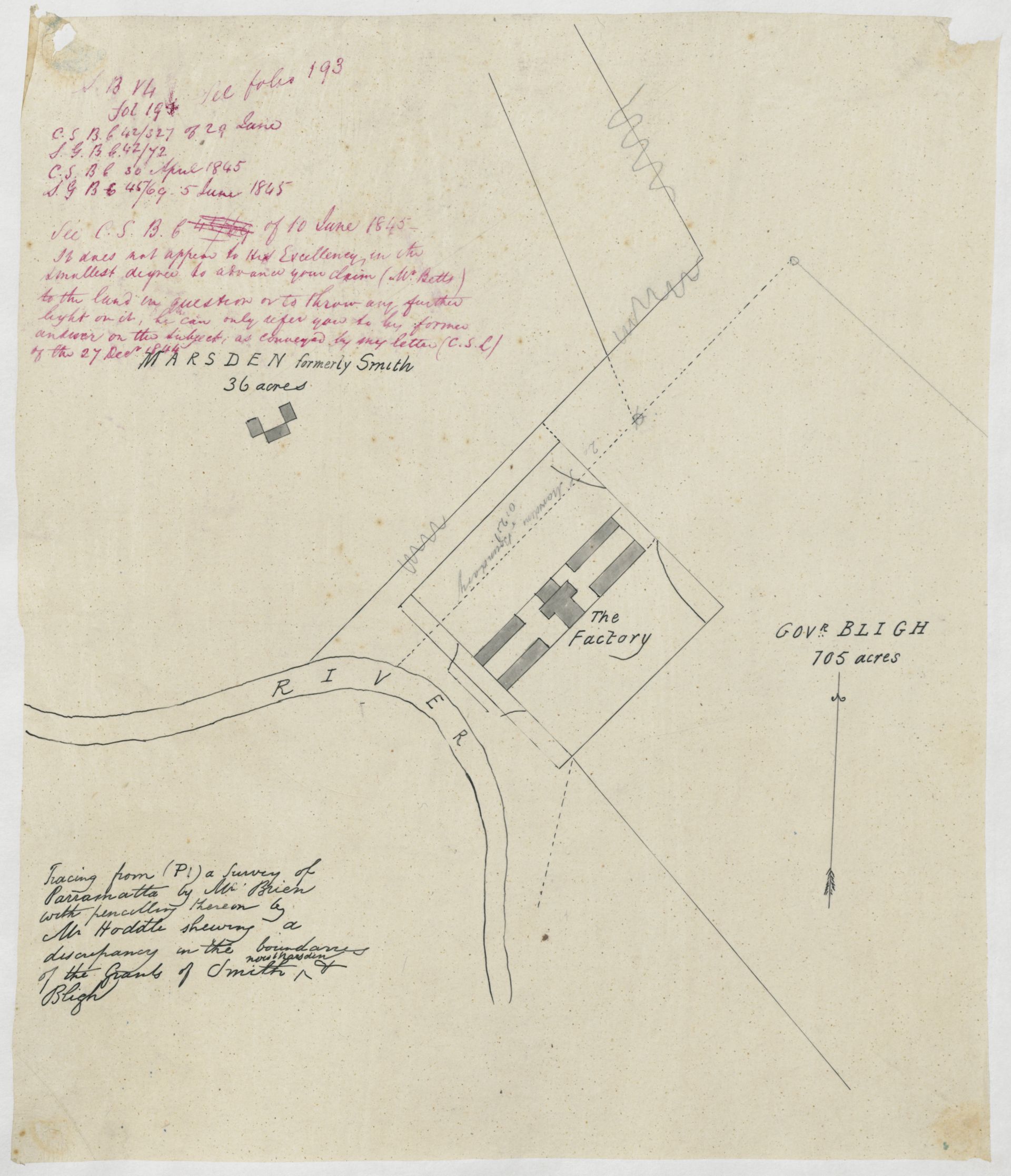

Properties ranged in size from 60 to 1,280 acres. Administration of the marriage portions scheme was slow, and it took six years for the land deeds to be finalised.

During this time, Hannah Tompson’s husband, Charles, became increasingly anxious about the legal status of his wife’s 60 acre marriage portion at Hunters Hill. Squatters occupied the Tompson’s land, and until the deeds were executed, Charles was unable to evict them. Complicating the situation further, was that the Tompson marriage had not produced children. It was therefore uncertain what would happen to the property in the future.

By 1831, the State ceased to grant land freely and Governor Darling’s marriage portions scheme, which he had introduced in 1828, came to an end. The initiative—which had both supporters and detractors—had been shortlived. The idea that married women could own property separate to their husband would not reappear for another 50 years. Darling’s marriage portions scheme was part of an expansive practice of granting land to advance the British Crown’s colonisation of NSW. Post-colonial understandings of this uncover other perspectives, including the impact on Australia’s Indigenous people.

Content first published in the Marriage: Love and Law exhibition catalogue